Australia’s medicines regulator has approved a new drug to treat the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, but experts warn that less than one in five people with dementia will be eligible for the treatment that could cost more than $80,000 out of pocket.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) has registered donanemab, sold under the brand name Kisunla and developed by pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly, for the treatment of adults with early symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease who have a specific genetic profile.

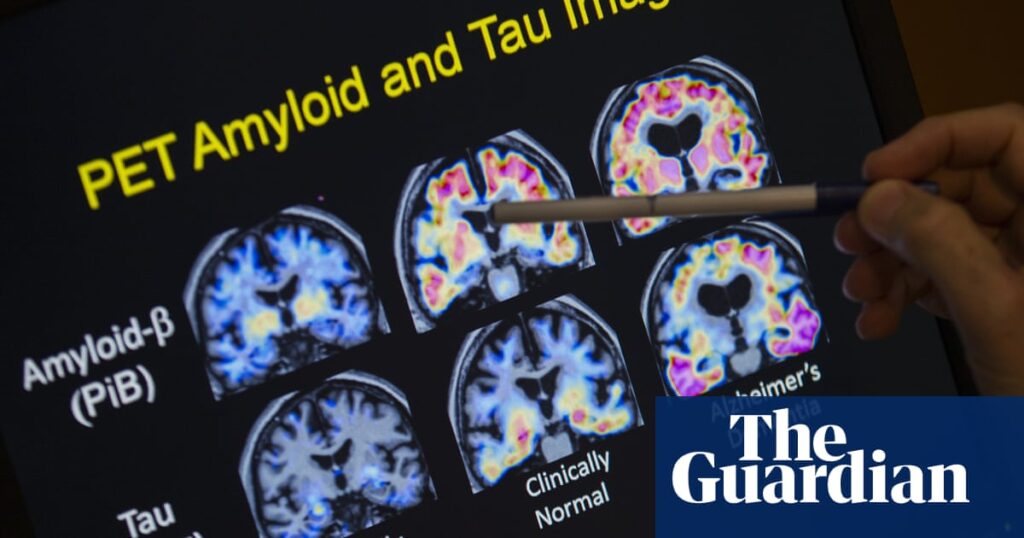

Donanemab is given as an intravenous infusion through the arm every four weeks for a maximum of 18 months, and works by targeting amyloid proteins in the brain – the buildup of which researchers believe contributes to Alzheimer’s disease.

The registration marks the first new treatment for Alzheimer’s disease in 25 years, and the first time a treatment affects the outcome of the disease, Prof Christopher Rowe, the director of the Australian Dementia Network said.

The medications that were approved 20 years ago temporarily improved symptoms, “but this one actually slows down the rate of decline by about one-third,” Rowe said.

While this is a “significant first step” in the hope to eventually use a combination of medications to stop the progression of the disease, Rowe warned “expectations may be a bit high because most people with Alzheimer’s disease won’t actually qualify for this”.

To be eligible for the medication a person has to be in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, the mild cognitive impairment phase, and not be susceptible to the drug’s risk factors, he said.

“The biggest impediment is people being diagnosed too late if they are already beyond the very early stage of Alzheimer’s disease.”

The drug has also been associated with the side effects of brain swelling and bleeding, which occurs at a much higher incidence in people who carry two ApoE ε4 genes.

The TGA registration excludes people who carry the genes, which Rowe said is an “unfortunate situation” as the gene variant itself elevates the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease younger, often in their 60s.

Before starting the therapy patients must be tested to determine their genetic status and have MRI scans to detect any initial signs of brain bleeding and swelling that might make it unsafe to have the drug. Patients also need to receive continuous MRI monitoring for any brain bleeding while they are on the treatment.

“We actually estimate that only about 10 to 20% of people with dementia will be suitable for the drug, but that is still a huge number given there’s 400,000 people in Australia with dementia, and probably 40,000 diagnosed every year,” Rowe said.

To qualify for the treatment, patients will also have to have their early Alzheimer’s diagnosis confirmed via a lumbar puncture or an amyloid PET scan, which can confirm the presence of amyloid proteins – neither of which are covered by Medicare. The drug is not on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).

“This treatment will cost probably $80,000 and an individual currently will have to pay that out of pocket. The drug itself is probably going to be about $40,000 but then there’s specialist fees, infusion fees, MRI scans and amyloid PET scans to pay for as well.”

after newsletter promotion

Eli Lilly has applied to include Kisunla on the PBS which will be reviewed by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) in July.

The health minister, Mark Butler, on Thursday said “there is still a fair way to go, though, to determine whether or not this will be reimbursed by the federal government and, if so, for which patients”.

“There will also need to be consideration of the associated scanning that needs to take place for patients.

“A bit of a way to go but very exciting news for the Alzheimer’s community,” Butler said.

There has been controversy among researchers whether slowing down the rate of decline by a third is significant enough to warrant the risks this class of drug carries.

Rowe said “the patient and their family have to be fully informed that they have to make that decision. It’s probably buying them a couple of years extra before they get to the severe dementia stage, and they’ve got to decide whether the money and the risks are worth that.”

Dementia Australia CEO Prof Tanya Buchanan said “with dementia the second leading cause of death of Australians, and the leading cause of death of Australian women, we welcome any steps taken towards improving the lives of people living with dementia, their families and carers.”

The Australian Dementia Network is running a trial of GPs being able to give blood tests to confirm Alzheimer’s disease, which would help build the capacity of doctors who can diagnose and allow people to get treatment sooner.